Leucobrephos brephoides is a rare moth species in the family Geometridae, subfamily Archiearinae. I have seen it only once, back in March 2006. Even though I look for it every year in late March and early April, I have not found it again.

The one and only time I have seen it, there was still snow on the ground, although it was melting. In the marsh where it was resting on some grass, a flood was beginning. And it was chilly, in the mid-30s to low-40s F. For Leucobrephos brephoides, this was a normal day.

I was excited to find this little moth. It was cold and there was still snow on the ground. I’d never really thought of insects being active so early. Since then, I have found that many insect species, beetles, moths, wasps, and midges, are active this early. Even spiders are out. Some insects are feeding on nectar and pollen from early-flowering willows. Others are seeking mates. A few, along with the spiders, are hunting other insects.

Description

The forewing of Leucobrephos brephoides is black and dusted with grey. The postmedial line is black with a white border. The antemedial line is also black but lacks a white border. The hindwing is white with an even black margin and basal black scaling.

Males have pectinate (feathery) antennae, the females have filiform (thread-like) antennae.

Life history

In the spring, female Leucobrephos brephoides lays 1 to 3 eggs on a leaf scar near the tips of aspen branches. They may lay their eggs thirty or more feet from the ground or just a few feet from the ground. After about 15 days, the eggs hatch. The larvae go through five instars before burrowing into the soil and pupating.

In the spring, the adults emerge from their pupa. Adult Leucobrephos brephoides are day fliers and active even while temperatures are still cold and snow is still on the ground.

Habitat and host plants

Leucobrephos brephoides inhabits open mixed broadleaf and coniferous forests. Its primary host plant is quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), but it also feeds on paper birch (Betula papyrifera) and alder (Alnus incana). Larvae have also been found feeding on willow (Salix spp.) and balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera). All of these species produce catkins in the early spring before their leaves emerge. Catkins may be an important food source Leucobrephos brephoides larvae, which hatch from their eggs before leaf emergence.

Leucobrephos brephoides is found in cool northern forests where its primary host plant, quaking aspen, grows.

What do the adult moths eat?

Gibson and Criddle (1916) made some interesting observations about the food preferences of the adult Leucobrephos brephoides. They found that sugar baits did not interest the moths. Instead, they noted that rotten meat was attractive. The moths also sought moisture and could be found on muddy roadways near aspen woods.

Similar species

A similar species, also active when Leucobrephos brephoides is in flight, is Archiearis infans. Archiearis infans is more common and widespread than Leucobrephos brephoides. It has bright orange underwings. I’ve seen this species one time also, and that was in the spring (April 2021) during the day at a mud puddle. It lays its eggs in the spring, and the larvae feed on the same plants as Leucobrephos brephoides.

Other Leucobrephos species

Leucobrephos is a Holarctic genus with two species: Leucobrephos brephoides in the Nearctic and Leucobrephos middendorfii in the Palearctic. Leucobrephos middendorfii occurs in Siberia, Mongolia, and the Ural Mountains. The species Leucobrephos mongolicum is considered a synonym of Leucobrephos middendorfii, as is Leucobrephos middendorfii ussuriensis. The subspecies Leucobrephos middendorfii nivea is considered valid. Host plants of Leucobrephos middendorfii are from the same genera as those of Leucobrephos brephoides.

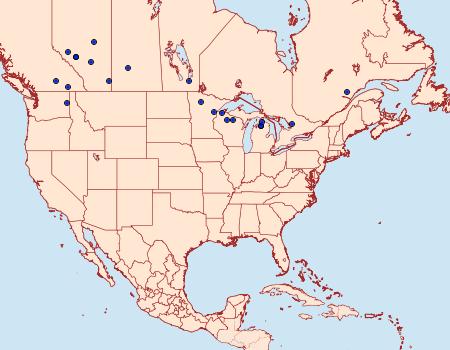

Range of Leucobrephos brephoides

Next year

Next March and April, I’ll be out looking for Leucobrephos brephoides again. I’ll check the edges of the woods and marsh for moths, as I have in previous years. I’ll also check the aspen and willows for eggs and larvae. I’m also going to set out bait stations, some with sugar to mimic sap and others with spoiled meat. Maybe after twenty years, I will finally see this scarce moth again. Or maybe not. It is possible that since 2006, the climate here has gotten too warm for this cold-loving species.

Sources

- University of Alberta E.H. Strickland Entomological Museum: Leucobrephos brephoides

- Gibson, A. and Criddle, N (1916). The Life History of Leucobrephos brephoides Walk. (Lepidoptera). The Canadian Entomologist, Volume 48, Issue 4, April 1916, pp. 133 – 138

- Moth Photographers Group: Leucobrephos brephoides

- Moth Photographers Group: Archiearis infans

- BugGuide: Leucobrephos brephoides

- BugGuide: Archiearis infans

- Müller, Bernd, Erlacher, Sven, Hausmann, Axel, Rajaei, Hossein, Sihvonen, Pasi, and Skou, Peder. (2019). New species for the fauna of Europe after publication of the previous volumes. DOI: 10.1163/9789004387485_009. (182. Leucobrephos middendorfii (Ménétriés, 1858)).

- Vojnits, A. (1977). Archieariinae, Rhodometrinae, Geometrinae II, Sterrhinae II and Ennominae III (Lepidoptera, Geometridae) from Mongolia. Annales historico-naturales Musei nationalis Hungarici, 69, 165–175.