In an earlier post, I wrote about Williams’ tiger moth (Apantesis williamsii). In this one, I present two more Apantesis species: Apantesis phalerata (Harnessed Tiger Moth) and Apantesis virgo (Virgin Tiger Moth).

Most Apantesis moths are characterized by dark forewings and numerous, often parallel, crisscrossing white or off-white lines. The patterns are usually distinctive enough to determine species, but not always.

What’s in a name?

The genus name Apantesis is from the Greek word “apantēsis”, translated as “meeting, an encounter/reply” and “to meet face to face“. It describes a custom of meeting visiting dignitaries where citizens would gather to welcome and escort the dignitary or hero in a procession. I’m not sure why this word was used to name the genus.

Harnessed Tiger Moth (Apantesis phalerata)

Harnessed Tiger Moth (Apantesis phalerata) is part of a group of similar species that includes Apantesis nais, Apantesis carlotta, and Apantesis vittata. Characteristics of the forewing pattern overlap in all four species, making accurate determination difficult, if not impossible, from a photograph. Had this moth spread its wings, exposing the underwings, then the choice might have been between Apantesis phalerata and Apantesis carlotta. Or maybe not.

Genital dissection is considered to be the only reliable way to determine these Apantesis species accurately, but I’m not willing to chop up a moth that rarely gets this far north. I’m just going to call my moth Apantesis phalerata because it looks more like identified specimens than it does the other three species. Additionally, the orange thorax appears to be another characteristic in photos of moths identified as Apantesis phalerata, distinct from the other three. Of course, I could be completely wrong.

Virgin Tiger Moth (Apantesis virgo)

Identifying Virgin Tiger Moth (Apantesis virgo) is not as fraught as it is with Apantesis phalerata. Apantesis virgo is a large white, black, and red moth, 20 to 27 mm long. Black in color, the forewing has distinct off-white veins and transverse lines in the postmedial and subterminal areas. The hindwing may be bright pink, red, orange, or occasionally yellow, with an antemedian and outer margin lined with a row of black spots. There is also a patchy marginal band.

Larvae and host plants

Larvae of Apantesis moths are similar in appearance. Black and bristly, Apantesis virgo larvae have orange-brown spiracles; the setae beneath the spiracles may be orange. Brown to black bristles cover the black larvae of the Apantesis phalerata, which frequently have a pale dorsal line. Larvae of both species feed on low-growing herbaceous plants.

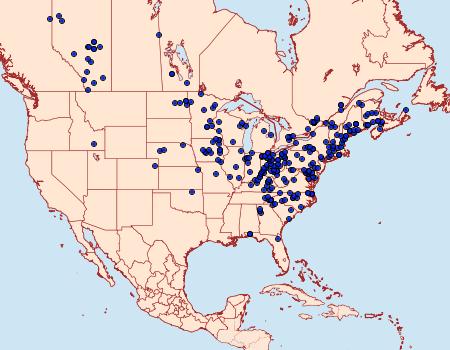

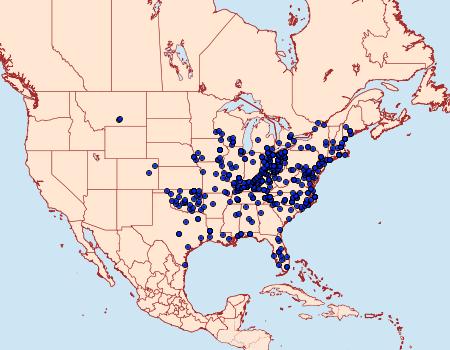

Range and distribution

The following two maps from the Moth Photographers Group show the range and distribution of Apantesis virgo and Apantesis phalerata.