Recently, I’ve become more interested in leaf mining insects after finding what might be the serpentine leaf mine of a Stigmella moth in a blackberry leaf. This wasn’t the first moth leaf mine I have found. In 2017, I identified another leaf mining moth, Phyllocnistis populiella, recognizing it from its leaf mine in a balsam poplar leaf.

Later, in 2019, I found the adult of another poplar leaf mining species, Phyllonorycter nipigon. Beyond that, my findings of leaf miners have been sporadic and by chance when photographing micro-moths at my moth lights.

Changing weather, changing focus

With the colder fall weather, it is more difficult to find insects and other arthropods. So, now I am turning my attention to the signs of them.

Out on my walks in the woods late last month, I came across five more serpentine leaf mines. The first was in a big-leaf aster (Eurybia macrophylla), which is shown in the photo at the top of the page. The other four were in wild red columbine (Aquilegia canadensis), coltsfoot (Petasites palmatus), goldenrod (Solidago gigantea), and bunchberry (Cornus canadensis). I couldn’t find larvae in any of them, but I think I have a good idea of what made them.

Possible identifications

The leaf mine in the aster leaf was probably made by the larva of a species of fly in the genus Ophiomyia, leaf mining flies in the family Agromyzidae.

While I’m not absolutely certain, the leaf mines in the other four plants were probably made by the larvae of leaf mining flies in the genus Phytomyza, also in the family Agromyzidae.

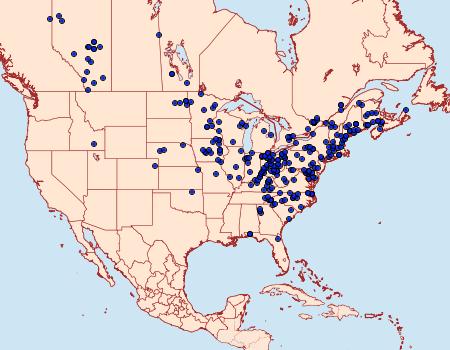

- Columbine: Phytomyza aquilegivora

- Bunchberry: Phytomyza agromyzina

- Coltsfoot: Phytomyza albiceps group (see page 5)

- Goldenrod: Phytomyza solidaginophaga

I’ve probably seen the adult Phytomyza flies, but didn’t give them a second thought, assuming they were just some more pesky flies buzzing around my head looking for blood or sweat. Next year, I’ll be paying more attention.

Leaf mining flies are species-rich

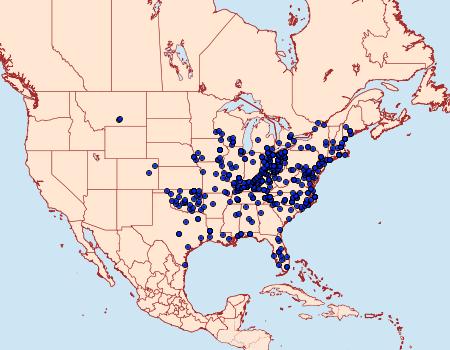

There are at least 600 named species of Phytomyza, making it the largest genus of leaf mining flies in the world. Ophiomyia has over 200 species. Species of Phytomyza and Ophiomyia are host-specific, which accounts for much of the diversity in their genera.

Cerodontha is another species-rich leaf mining fly genus in the Agromyzidae, with 285 species worldwide. Cerodontha is a monocot specialist mining the leaves of sedges (Cyperaceae), soft rushes (Juncaceae), irises (Iridaceae), and grasses (Poaceae). Some Cerodontha species have been found in Minnesota and neighboring Wisconsin.

A quick search of species of Phytomyza and Ophiomyia that might occur in northern Minnesota shows at least twenty species and five species, respectively. The number of Cerodontha species in Minnesota is unknown. I think next summer is going to be an interesting one.

Further Reading

- A new species and taxonomic notes on northern Nearctic Cerodontha (Icteromyza) (Diptera: Agromyzidae). Boucher, S. (2008). The Canadian Entomologist, 140(4):557-562.

- Revision of Nearctic species of Cerodontha ( Icteromyza ) (Diptera: Agromyzidae). Boucher, S. (2012). The Canadian Entomologist 144(01):122-157

- Species and Cultivar Influences on Infestation by and Parasitism of a Columbine Leafminer (Phytomyza aquilegivora Spencer). Braman, S. K., Buntin, G. D., and Oetting, R. D. (2005). Journal of Environmental Horticulture. 23(1):9–13.

- Nantucket’s Neglected Herbivores II: Diptera. Eiseman, Charles S., and Julia A. Blyth (2022). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington, 124(3):564-605.

- Studies on Boreal Agromyzidae (Diptera). II. Phytomyza miners on Senecio, Petasites, and Tussilago (Compositae, Senecioneae). Griffiths, Graham C. D. (1972b). Quaestiones Entomologicae, Volume 8:377-405.