In an earlier post, I wrote about Lophocampa maculata, a moth in the Arctiinae, distinguished by its fuzzy black and yellow larvae. These larvae later metamorphose into beautiful adult moths with a contrasting pattern of alternating bands of warm, muted golden-orange and darker brown markings with a reddish-orange tinge. In this post, I write about Halysidota tessellaris, the banded tussock moth, another moth in the Arctiinae.

Identification

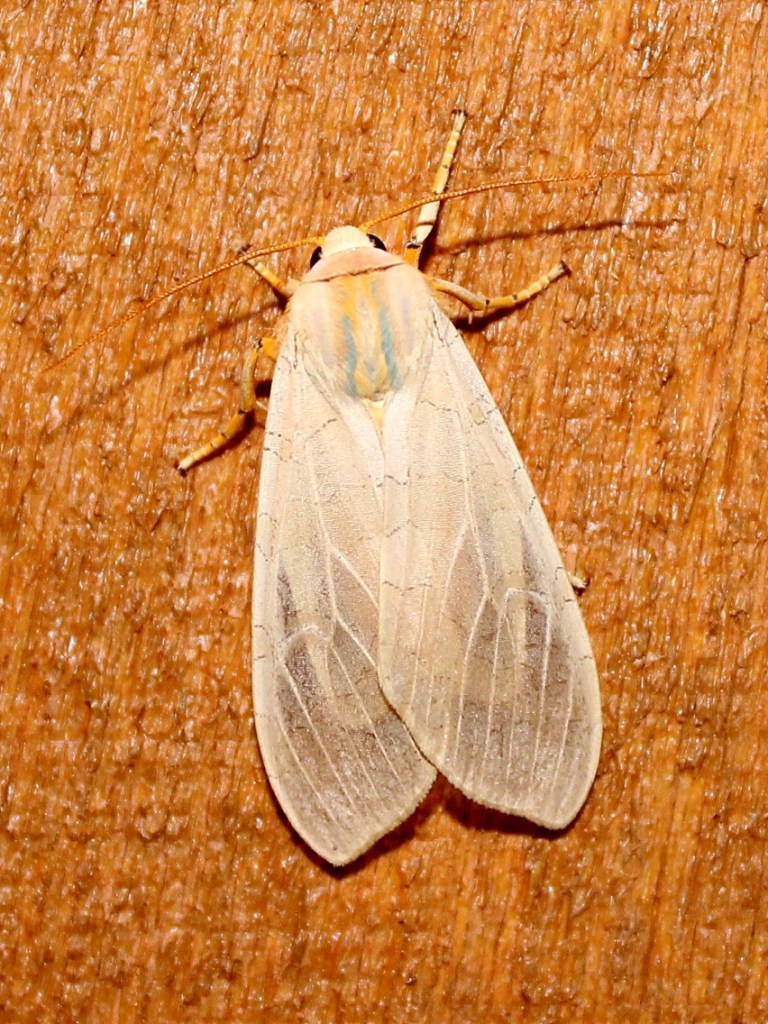

Like Lophocampa maculata, the larvae of Halysidota tessellaris are also fuzzy, but they are usually gray to dingy brown with long white and long black tassels. The adult moth, while similar in size to Lophocampa maculata, has translucent yellow forewings marked with slightly darker bands and irregularly shaped block-like cells that form a tessellated pattern. Also, there are two parallel blue stripes on the fuzzy thorax.

Life cycle

Across its range, larvae of Halysidota tessellaris feed on many species of hardwood tree leaves. Among these are box elder (Acer negundo), sweet birch (Betula lenta), ash (Fraxinus spp.), oaks (Quercus spp.), and many others. Adult moths take nectar and are pollinators of milkweeds (Frost, S. W. (1965) Insects and Pollinia. Ecology, 46. 556-558, paywall).

Similar species

Adults of the related Halysidota harrisii (sycamore tussock moth) are similar in appearance to Halysidota tessellaris. Where the ranges of Halysidota tessellaris and Halysidota harrisii overlap, genital dissection is necessary to determine the species. Halysidota harrisii larvae, which may be solid white, yellow, orange, or gray, feed exclusively on sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) leaves. The ranges of sycamore and the moth coincide closely.