Sceptridium multifidum, the leathery grape fern, is similar to Sceptridium rugulosum (St. Lawrence grape fern), which was covered in an earlier post. At one time, Sceptridium rugulosum was considered a variation of Sceptridium multifidum and was named Botrychium multifidum forma dentatum.

Description

Segment blades of Sceptridium multifidum are flat, rounded, with entire to shallowly denticulate margins and blunt tips. The texture is leathery. The fronds can be large, measuring 25 by 35 cm.

Habitat

Sceptridium multifidum grows in old fields, the edges of woodlands, and in open forests. Often, there will be dozens of plants growing at a single location. Sceptridium rugulosum and Sceptridium dissectum may also be present.

They live a long time

Like Sceptridium rugulosum, Sceptridium multifidum can live for many decades (Stevenson 1975). The ferns in the photos with the larger fronds were first seen by me around 1994. Even then, the fronds were large. I excavated two medium-sized plants in 1995 and counted the leaf scars on the stems. They had about 25 leaf scars each. If Sceptridium produces one frond per year, then those two plants were 25 years old. So, it is possible that the other larger ferns were also 25 years old or older, making these in the photos at least 55 years old.

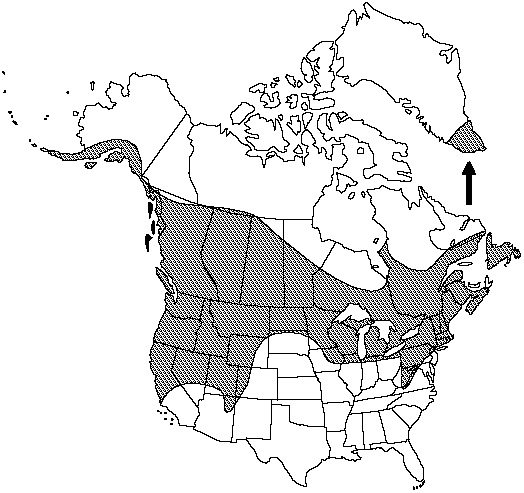

Range

Sources

- Flora of North America: Botrychium

- Flora of North America: Botrychium multifidum

- Olson, Elizabeth K. (2020). Botrychium multifidum Rare Plant Profile. New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection

- Stevenson, Dennis Wm. (1975). Taxonomic and Morphological Observations of Botrychium multifidum (Ophioglossaceae). Madroño Vol. 23: 198-204.