This peculiar growth on a tree branch in the above photo is Arceuthobium pusillum (dwarf mistletoe), a parasitic plant that grows on black spruce (Picea mariana) trees. It is a flowering plant and a member of the same family (Viscaceae) as the familiar Christmas mistletoes, Phoradendron leucarpum and Viscum album. But at 2 to 3 mm in size, it is much smaller and unlikely to feature in any Christmas decorations.

Description

Arceuthobium pusillum is a minute perennial shrublet parasitic on the branches of bog conifers, primarily back spruce. Although photosynthetic to a limited extent, all of its other nutritional needs are derived from the host plant.

The stems of the Arceuthobium pusillum are green, orange, red, maroon, or brown, 2 to 3 cm long, and covered in small oppositely arranged, scale-like leaves.

The staminate (male) flowers are represented by three or four sepals, each with a sessile anther sac. There may be a prominent nectary in the center of the flower.

Pistillate (female) flowers have reduced sepals fused to the outside of the bicarpellate gynoecium. Mature pistillate flowers exude a pollination droplet that draws in the pollen grain.

Reproduction

Flower buds are formed in the fall. Flowering occurs in the spring. The minute flowers are either pistillate or staminate and borne on separate plants. Pollination is accomplished by insects and by wind.

The most frequent pollinating insects are flies (Syrphidae, Tachinidae), beetles (Lampyridae), and wasps (Aphidiidae, Ichneumonidae, Tenthredinidae, Vespidae). In studies where insects were excluded from access to the flowers, the seed set was lower.

The 2 to 3 mm long greenish or brownish fruits contain one seed. At maturity, pressure builds up in the fruit, causing the seed to be ejected up to 12 or more meters. The seeds are sticky, which helps them adhere to a potential growth site. If they land on a young live spruce twig and germinate, root-like growths (haustoria) push through the bark and into the cambium. It may take two or more years of growth under the bark of the host tree before the first mistletoe shoots appear.

The sticky seeds may also adhere to the feathers of birds, thus aiding in long-distance dispersal to new bogs with black spruce. After the seed is ejected, the mistletoe branch dies.

Witches’ brooms

The mistletoe alters the growth of the trees’ twigs by causing a loss of apical dominance. As a result, clusters of branchlets form, called “witches’ broom”. This alteration may also affect the growth form of larger side branches that develop from the witches’ broom. These branches are twisted and flattened into an oval shape.

Abundant growth of Arceuthobium pusillum on spruce can eventually kill the tree. But the witches’ brooms, whether living or dead, are shelter for many insects, spiders, birds, and small mammals.

Habitat

Arceuthobium pusillum is a parasitic plant that grows on black spruce trees in poor fens, intermediate fens, and coniferous forested peatlands. It is occasionally found on white spruce (Picea glauca) and red spruce (Picea rubens). It rarely occurs on tamarack (Larix laricina), white pine (Pinus strobus), jack pine (Pinus banksiana), red pine (Pinus resinosa), and balsam fir (Abies balsamea).

Arceuthobium pusillum has parasites, too

Caliciopsis arceuthobii is a fungus that infects the flowers of spring-flowering Arceuthobium species, including Arceuthobium pusillum. Its spores are spread by wind and by insects visiting the flowers. The fungal hyphae destroy the developing fruit.

Discovery of the species

Thoreau first described the brooms formed by Arceuthobium pusillum in 1858, although he did not know the cause of them. In his journal entry, he wrote,

“About the Ledum pond hole there is an abundance of that abnormal growth of the spruce–Instead of a regular free & open growth–you have a multitude putting out from the summit or side of the stem of slender branches crowded together & shooting up nearly perpendicularly–with dense fine wiry branchlets & pine needles which have an impoverished look–all together forming a broom-like mass–very much like a heath.”

Arceuthobium pusillum was not formally described until 1872 by C. H. Peck after he received correspondence about the plant and specimens from botanist Lucy B. Millington of Warrensburg, New York, in 1871. Her correspondence about her discovery of a tiny mistletoe on Abies nigra (an older name for Picea mariana) was published in the Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. She wrote,

“I believe it to be a mistletoe. I found the first specimen in a small tree in the edge of a cold peat bog in Warrensburg, Warren Co., N.Y. In a few days I found more in a similar situation in Elizabethtown, Essex Co., N.Y. Later I found it halfway up the side of a small mountain. In every case the limbs of the trees infested were very much distorted. Every twig bristled with the little parasite…”

Range

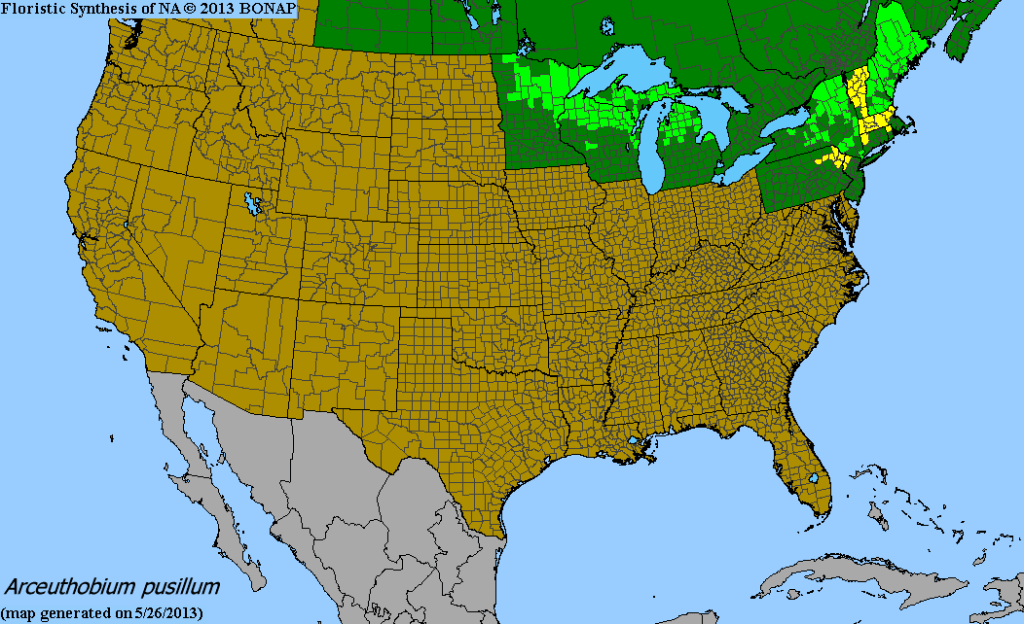

The range of Arceuthobium pusillum is from Newfoundland to Saskatchewan and south into New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and the Great Lakes states, closely following the range of its primary host, black spruce.

Sources

- MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program: Eastern Dwarf Mistletoe

- Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program: Dwarf Mistletoe Arceuthobium pusillum

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection: Arceuthobium pusillum Rare Plant Profile

- The Parasitic Plant Connection: Life Cycle of Arceuthobium (dwarf mistletoe)

- Minnesota Wildflowers: Arceuthobium pusillum (Eastern Dwarf Mistletoe)

- Flora of North America: Viscaceae

- Northern Poor Conifer Swamp (Minnesota DNR)

- Hedwall, Shaula J. and Mathiasen, Robert L. (2006) “Wildlife use of Douglas-fir dwarf mistletoe witches’ brooms in the Southwest,” Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 66: No. 4, Article 6.

- 1858 Journal of Henry David Thoreau (see pages 92-93)

- Millington, Lucy (1871). “New Mistletoe”. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 3: 43–44 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Geils, Brian W.; Cibrián Tovar, Jose; Moody, Benjamin (2002). Mistletoes of North American Conifers. General Technical Report RMRS–GTR–98. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 123 p.