Tag: nature

Finding Williams’ Tiger Moth in Minnesota

In a previous life, I searched for and documented rare plant species. But I was always curious about everything in nature, so I made it a point to learn as much as I could about all the things in the forests, glades, lakes, and swamps I explored. Sometimes I would make an interesting discovery, like the moth in the above photo.

I find a new moth

A few years back, while on a rare plant survey, I found a tiger moth that I later identified as Apantesis williamsii (Williams’ Tiger Moth). I found the moth in Cook County, Minnesota, in the Superior National Forest (SNF). It was simply lying in the middle of an old logging road just waiting to be found, I guess.

I’d never seen a moth quite like this one. I photographed it (I would have anyway no matter if it was new to me or not) and took some notes about the surrounding area. Then I GPS-ed the location, which is about 20 miles south of the US-Canadian border.

Because blueberry pickers were using the road that day, I carefully moved the moth to a safe spot. Then I got back to that day’s mission, searching for rare plants in the forest and the rare Nabokov’s blue butterfly (Lycaeides idas nabokovi). It might have been in the area as its larval host plant, Vaccinium cespitosum (dwarf bilberry), grew nearby in a prescribed burn. I found plenty of dwarf bilberry that day, but no sign of Nabokov’s blue butterfly. Not even a caterpillar.

Not a common species in Minnesota

Apantesis williamsii is uncommon in Minnesota. It appears that there are only two records before 2018. One record is from Cook County, the same county where I found this one, up in the northeastern corner of the state. The other is from Lake of the Woods County in the Northwest Angle, right on the US-Canadian border, found in 2017.

Since then, additional sightings of Apantesis williamsii have been made. Two other sightings (here and here) were made in Minnesota in 2018, but from northern St. Louis County, about 50 miles west near Ely, and also close to the Boundary Waters and Canada.

Globally secure

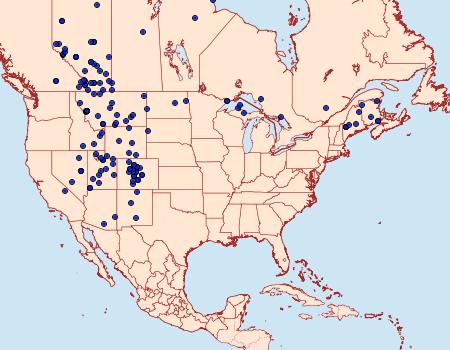

This is not a rare species globally, but based on the small number of sightings, it appears to be uncommon in Minnesota. Most records of Apantesis williamsii are from the Cordillera, starting in Saskatchewan, Canada, and then south through Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, California, Nevada, Arizona, and New Mexico in the western US. It occurs sporadically elsewhere, with scattered reports from Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, and New Brunswick in Canada, and in Michigan and Maine in the US.

Habitat preferences

In the main part of its range, Apantesis williamsii can be found in mountain meadows at middle to high elevations. It also occurs in quaking aspen forests and dry coniferous forests with sandy soil. The latter isn’t too different from the site where I found it. This was in a forest of aspen, birch, spruce, and fir with some jack pine and white pine on sandy soil. The weather is also cool in the summer, although climate change may upend that.

What does it it eat?

Larval food plants of Apantesis williamsii are not known, but it may feed on low-growing herbaceous vegetation like other species of Apantesis.

Syrphid Flies: Mimics, Pollinators, and Predators

This was an unusual sight. Three species of syrphids, each on a separate wild sunflower head, are getting a meal of pollen and nectar. Two of the species I could identify are Eristalis dimidiata (upper right) and Eristalis transversa (lower right). The third one in the upper left didn’t show enough details. I could only place it as possibly a Syrphus sp.

A swarm of bees?

I first got interested in syrphid flies about two decades ago when I was doing an inventory of plant species in a fen. Suddenly, I became aware of what sounded like a swarm of bees in a large patch of nodding bur-marigold and asters. To my relief, they were not bees but hundreds of syrphid flies nectaring at the flowers. Over the years, I’ve gradually learned more about these bee-like insects and their importance.

When to see them

Late summer is one of the best times to observe syrphid flies. You can see them on sunflowers, coneflowers, goldenrods, joe-pye-weed, bur-marigolds, and asters, all members of the aster family. Buzzing loudly, they go from flower to flower like bees, and with the bees, in search of pollen and nectar.

Syrphid flies can also be seen in spring and early summer. But to see them, you may need to go into the woods. Some of these forest-dwelling species can be attracted to sugary baits painted on tree trunks or boards attached to posts. They can also be found on woodland wildflowers like Canada mayflower.

Bee and wasp mimics

Many syrphids have body patterns and body shapes that resemble those of bees and wasps. This mimicry (Batesian mimicry) is a form of camouflage to deter potential predators. The resemblance to wasps and bees is striking.

Physocephala furcillata, Eumenes crucifera, and Doros aequalis resemble potter’s wasps, and Ocyptamus fascipennis, an ichneumon. Sericomyia chrysotoxoides looks like a yellow jacket wasp, and Eristalis flavipes could be mistaken for a bumblebee.

Syrphids are pollinators

Like bees, syrphids are pollinating insects. But it is not just aster family plants they seek out. I have seen syrphids on mustard (Brassica nigra), amaranth (Amaranthus cruentus), milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), purple prairie clover (Dalea purpurea), grass-of-parnassus (Parnassia sp.), and cinquefoil (Potentilla recta).

Not just pollinators but predators and recyclers

Syrphids do more than visit flowers. The larvae of many species are important predators of aphids and other soft-bodied crop pest insects. Some larvae may eat 400 or more aphids in their lifetime.

Other species larvae (rat-tail maggots) live in mucky habitats, eating microorganisms in the detritus and so contribute to nutrient recycling.

Encouraging syrphids

Syrphid flies, like the bees and wasps they often mimic, are important parts of the pollinator fauna. They don’t sting or bite, but their appearances can give you pause.

Planting nectar-rich domesticated plants like buckwheat, sunflowers, coriander, and dill, and wildflowers. Even small patches will help them. From there, they can launch forays into gardens and fields, pollinating crop plants. Predatory species will lay eggs that hatch into maggots that eat pest insects like aphids, scale insects, and spider mites.

Further reading

Field Guide to the Flower Flies of Northeastern North America. Jeffrey H. Skevington, Michelle M. Locke, Andrew D. Young, Kevin Moran, William J. Crins, and Stephen A. Marshall. (ISBN: 9780691189406. Published: May 14, 2019. Copyright: 2019.)

Another insect added to the checklist: a gall-forming fly

It might be getting colder outdoors, but there are still insects to be found. While out walking a few days ago, I came across this odd growth on a Dryopteris cristata (crested wood fern) frond.

This tightly coiled knot on the frond is caused by a galling insect that specializes in ferns. The species responsible for the gall is a fly (Diptera, Anthomyiidae) named Chirosia betuleti.

The fly’s larvae form galls on several fern species: Athyrium filix–femina (lady’s fern), Dryopteris carthusiana (spinulose wood fern), Dryopteris cristata (crested wood fern), Dryopteris filix–mas (male fern), Matteuccia struthiopteris (ostrich fern), and Pteridium aquilinum (bracken fern).

Another fern with a gall

A search for other galls the next day located one empty gall on the frond of a Dryopteris carthusiana plant in a tamarack swamp. I looked for Athyrium filix–femina and Matteuccia struthiopteris, but their fronds had already withered away now that it is fall. I’m sure I’ve seen these odd growths on them before. None of the Pteridium aquilinum plants had galls, and I don’t recall ever seeing them on the fronds before. There’s always next year.

Gall formation

The larvae of Chirosia betuleti feed on the trichomes (hair-like growths) along the midrib of the newly emerging frond, and then mine along the midrib, causing it to coil into a mophead shape. The related Chirosia grossicauda forms galls on bracken fern. Another insect to watch for next year.

The Anthomyiidae

Chirosia betuleti is a fly in the family Anthomyiidae (root maggot flies). Most species in this family feed on plants as larvae, feeding on roots, seeds, or mining leaves.

Some feed on dung, decaying plant matter, or mushrooms. Other species are endoparasitoids of grasshoppers, and some are kleptoparasites of Hymenoptera.

Adults feed on nectar and pollen and may be pollinators. Most species resemble small houseflies.

Range

Chirosia betuleti is reported on iNaturalist from the western coast of North America from Alaska to California, and inland to Saskatchewan, Canada, and Idaho, and Montana, around the Great Lakes and New England, then east to the Maritime Provinces of Canada. The range then follows the Appalachian Mountains south to the Great Smoky Mountains. There are two isolated occurrences in South Carolina and Florida.

Parasites of Chirosia betuleti

Larvae of Chirosia betuleti are parasitized by wasps in the genus Aphaereta (Braconidae) and the wasp genera Dimmockia and Elachertus (Eulophidae).