The blue wasp moth, Ctenucha virginica, is another moth in the Arctiinae (Tiger and Lichen Moths), like the woolly bear or Isabella moth. And like the woolly bear moth, its fuzzy larvae also overwinter, feeding briefly in the spring before pupating. They just don’t get as much attention as the woolly bears do.

Description

The descriptions below are based on my observations of this moth.

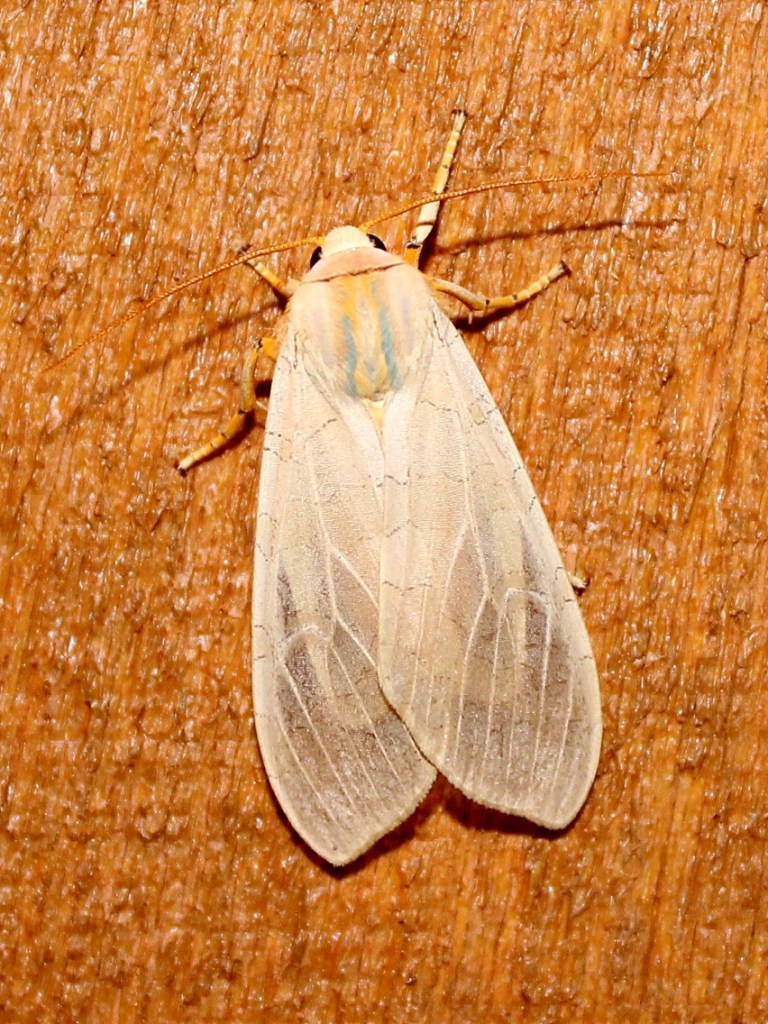

The adult Ctenucha virginica moths are large (wingspan 38 to 52 mm) with dark black (brown in older individuals as scales wear off) forewings fringed with white patches and darker black patches near the base and angle. The underwings are black and fringed in white. The abdomen and thorax are metallic blue, and the head is bright orange with black eyes. The antennae and legs are black. The antennae of males are fringed and comb-like.

The metallic blue color of the thorax and abdomen and the orange head of Ctenucha virginica mimics some species of blue wasps and so may serve to deter predators.

The larvae are are black and covered by tufts of short, yellow and white hairs. There is a white line along the sides under the fuzz. The fuzzy hairs of some individuals may be white. The legs are pink, which helps to distinguish white forms from similar-looking fuzzy white caterpillars.

When and where to see the larvae

Spring is the best time to find blue wasp moth caterpillars when they have emerged from hibernation and are feeding. In some years, they can be quite abundant. I have observed the larvae feeding on grasses, sedges, and iris in the spring. The preferred larval habitat is graminoid-rich wetlands, but I’ve also seen them in old hayfields, especially in damp areas.

Once, I found a Ctenucha virginica caterpillar feeding on frost lichens (Physconia sp.) growing on a black ash tree. It had climbed about 6 feet up the tree to get to this lichen. Below the tree grew the caterpillar’s usual food plants: iris, manna grass, and Carex species.

Living in wetlands is not without dangers. In the spring, they may flood, and the caterpillars could drown. Their fuzzy hairs do help them to float, but eventually, these become waterlogged. One spring during flood season, as I was walking through a flooded sedge marsh, I found several dozen Ctenucha virginica caterpillars floating in the water. I collected each one and moved them to some sedge tussocks that stood above the water. I hope that helped them out.

Pollinators

Ctenucha virginica moths are pollinators. Disguised in their wasp-like coloration, they fly during the day, nectaring at many kinds of flowers in upland and wetland sites.

They also drink dew from plant leaves. The one pictured below was drinking dew droplets from the leaves of American hazel (Corylus americana). American hazel is covered in sticky red glandular hairs, and I wonder if this, in addition to water, was what it was seeking. Perhaps there are chemicals in the glandular hairs it needs.

Active at night, too

Ctenucha virginica moths are frequent visitors to my moth lights. Last year, in late June and early July, they were in abundance, with ten or more each night. In the photos below are a few of the visitors I saw last summer.

More caterpillars this spring?

With so many Ctenucha virginica moths last summer I expect there will be an abundance of their caterpillars this coming spring. If there are then I will collect some so I can let them pupate in a safe environment and learn a little more about that stage of their life cycle.